When a man died in early Pennsylvania, most of the time his death set off a chain of legal events. Following procedures that were familiar from England, the survivors, whether Quaker or not, knew what they had to do. Within a few days of the death, an inventory was taken of his possessions: cash on hand, clothing, household goods and furniture, tools or farm equipment, livestock, grain growing in his fields. The men who took the inventory appraised the value of each item, and totaled up the worth of estate (not including the land).

In his will, if he left one, he named executors who were responsible for paying his debts and burial expenses, collecting debts owed to him, selling property if needed to cover the debts, making a distribution to the heirs, and making an account of the estate, starting with the assessed value of the inventory. They were supposed to file the account within a year after the death. In the case of a larger, more complex estate, it might take longer, and occasionally more than one account was necessarily filed.

If he did not leave a will, the administrators had the same responsibility as the executors. A surviving wife, if there was one, was usually the administrator, often assisted by a relative or friend. Sometimes in the will a Friend would specify that the monthly meeting should assist her.

Women did not usually make wills in the early years, and their estates did not go through this probate process. Her family would take care of her possessions and any debts, without any legal notice taken. There are some early exceptions. When the widow Agnes Crosdale died in 9th month of 1686, her sons William and John, along with Nicholas Waln and Robert Heaton, served as joint administrators, signing a bond to Phineas Pemberton the Deputy Register, and an inventory was taken of her estate.

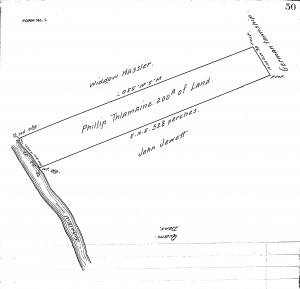

The death of a husband could be devastating to a woman. By law she was entitled to one-third of the estate, both land and personal goods (one-half if there were no children). This was called the “widow’s third”. If he left a will that gave her less than a third, she could reject it and claim her portion. However, if he left debts, the creditors had a claim to the estate that took priority over her claim. If the estate had to be sold to satisfy the debts, she might be left with nothing.

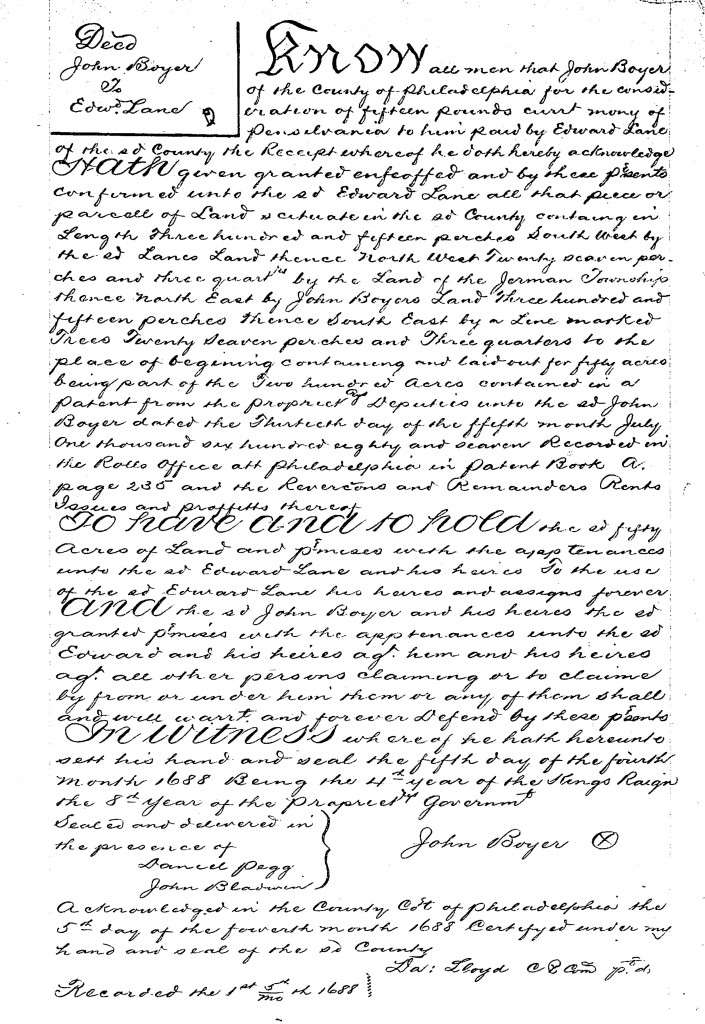

In practice many poor people did not leave a will. When there is one, it is valuable for the genealogist, since it usually tells the names of spouses and children and the residence when the will was written. It is equally valuable to the historian, as it gives proof that someone emigrated, tells whether the wife was entrusted with the estate, and occasionally tells stories. For example Robert Jeffs in his will proved 2nd month 1688 asked William Penn to take note of unfair treatment by Thomas Fairman over a leased farm. John Tathum cut his disobedient daughter Dorothy out of his estate because he disapproved of her clandestine marriage.

The other estate papers are valuable too, especially the inventories. These give a window into the homes and life of the people, listing how many beds they had, how many pots, how many barrels of food. They allow a historian to look at the wealth of the community: how evenly it was spread around, how it changed over generations, what form it took. Because the inventories are so detailed, they are a source of data that can be mined to answer many questions. How valuable were people’s clothes? How much cash did they keep on hand? How many cows did it take to feed a family?

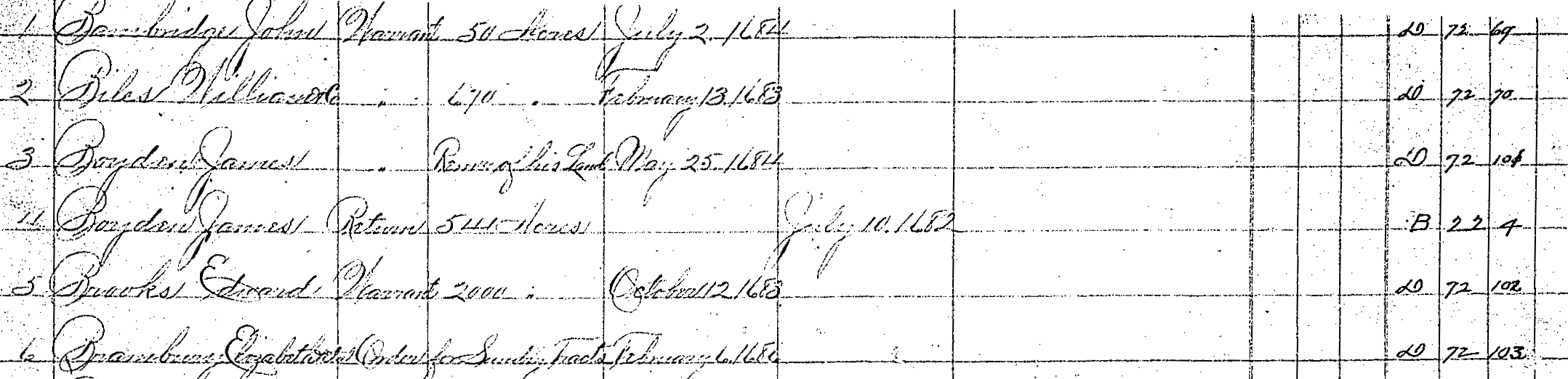

It is easy to access short abstracts of the early wills. For Philadelphia, Chester, and Bucks County they are available on the USGenWeb Archive. Note that Chester County did not register its own wills until 1714; until then they were handled by Philadelphia County. Bucks County registered some early ones until about 1693, then for twenty years they were handled in Philadelphia, then in 1713 they were again registered in Bucks County.

The Bucks County courthouse in Doylestown has the original estate packets, consisting of the administrative bond or will, inventory, and accounting of the estate. Many estates are missing one or more of these pieces, but the surviving papers are there. They will eventually be digitized, but for now if you want to see the full will or the other papers, this is the only source. Ancestry has an index: the Index of Bucks County wills and administrations to 1850.

The office of wills in City Hall in Philadelphia holds the original documents administered in Philadelphia County. There are three ways to see them, depending on how much detail you want to see. The wills were copied into will books, which are in the office. They were microfilmed and you can read them there. You can request the full estate packets, usually on a day’s notice, which are the only source for the inventory and account.

For Philadelphia County, the Historical Society of Pennsylvania has some valuable holdings. The photostats of the early wills and inventories are in a set of 25 volumes, to about 1725. (Call numbers Ph 1A:1, Ph 1A:2, etc.) They have some overlapping coverage in other volumes (Ph 3A, Ph 4A …) and an index at Ph 13A.

For Chester County estate documents, you will need to go to the Chester County Archive in West Chester. There is an online index, and a guide to the documents, available on their website. Remember that they do not have any estate documents before 1714.