When Thomas Holme arrived in the fall of 1682, the site for Philadelphia was already chosen. It was a fine location, 300 acres on the Delaware River, with abundant streams, a high bank, and a cove where small ships could land.

“Rising from either side of a natural, apparently centrally located watershed, many-branched steams flowed east and west into each river. At the southern end of the Delaware side, two of these streams emptied into the north and south extremities of the cove. Their water then coursed out into the Delaware through a narrow channel at the cove’s southern edge… Between the low sandy beach of the cove to the south… the Delaware’s banks rose gradually to a height of about thirty feet above the river, then shelved down abruptly to the Coaquannock.” 1

With the site chosen, the next step, and a tricky one, was to choose where different purchasers would have their land. At first the city lots were not for sale to “the general public”; they were a bonus for the First Purchasers, people who bought from Penn in England. There were 50 groups of First Purchasers, with each group paying for 10,000 acres. Each group was to receive a large city lot; if there were more than one buyer in a group, as there typically was, the lots would be subdivided. The plan was that the lots would be chosen and laid out by random drawing. The drawing was held on September 19, 1682. But before these lots could be laid out, word came that Penn was on his way from England and would arrive the next month. The layout could wait for his approval.

When he arrived, he found that many of the First Purchasers, including the majority of the largest ones, had not emigrated. This meant that, “Until these absentees came over, or sent agents or servants to develop their share of purchased land, eighty per cent of the town, as well as of the country land, would remain unimproved.” 2 This was undesirable from Penn’s standpoint; he wanted a thriving town as quickly as possible. The random drawing was probably not appealing to the purchasers as well, since they had no say in the location of their lots. So the plan was modified. Penn bought more land from the Swedes Peter Cock and Peter Rambo to open up a second river frontage on the Schuylkill. This expanded the city to 1200 acres and gave Penn a place to put purchasers who did not emigrate, “where their absence would be less noticeable.” 3

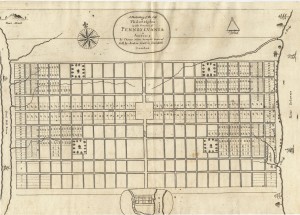

Thomas Holme’s next step was to lay out the grid of streets. The street facing the river Delaware was called Front Street, and this set the pattern for the other north-south streets — Second Street, Third Street, and so forth. The east-west streets were initially named for prominent men like the merchant James Claypoole, Thomas Holme and Thomas Wynne, a Welsh physician. These were soon renamed, as it was not in the Quaker spirit to honor individual men in this way. Today those are Walnut, Mulberry and Chestnut Streets.

Five open squares were cut into the grid, one in the center and one in each quadrant. The center square was to be for public buildings; in fact it still serves that purpose, as the site of City Hall. The other four squares were for public use. They were later named for Franklin, Washington, Rittenhouse and Logan, and still serve as parks today, although Logan Square turned into a circle when the Benjamin Franklin Parkway was laid out.

Now the lots could be laid out for purchasers. While he supervised this process, Holme also worked on drawing a map of the city, showing the rivers, the Dock, streets, and the five squares. Numbers on the map showed where lots were laid out. This map was called A Portraiture of the City of Philadelphia. It was published in 1683 as part of Penn’s letter to the Free Society, a group of investors, and was widely circulated. 4

The map was well-received in England. Philip Ford, one of Penn’s agents, wrote to Holme that, “As for the map of the city, it was needful it should be printed; it will do us a kindness, as we were at a loss for want of something to show the people.”

- Roach, “The Planting of Philadelphia, part 1, pp. 32-33 ↩

- Roach, p. 30. ↩

- Roach, p. 30. Soderlund, William Penn and the Founding of Pennsylvania, p. 205. ↩

- The map did not include the names of the lot-holders; there was an accompanying list. This should correspond to a list of First Purchasers, but there are many discrepancies. ↩