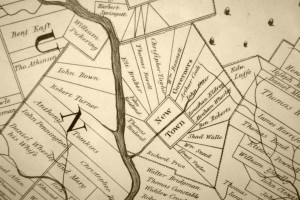

While Thomas Holme was busy serving in Penn’s government and supervising surveys, he was also working on his map of the countryside, the work for which he is still remembered today. This was more ambitious than his map of the city, covering over 200,000 acres. It was a magnificant achievement – at once a marketing tool, a piece of propaganda, a geographical representation, and a record of land ownership. It has been reprinted in countless state, county and township histories. It purports to show the ownership of most of the land in the three counties, and if accurate, serves as the starting point for the chain of ownership to the present day.

It is not fully clear why Penn wanted the map. It could have been a marketing tool to show prospective buyers, except that much of the land was already sold and settled by 1687, as the map itself showed. Perhaps he wanted it to show absentee owners where their land was situated. As we will see later, a substantial number of the owners on the map did not emigrate, and never saw their land in person. The map also served to promote the colony to potential investors, those merchants who might provide capital for business and trade.

To make the map, Holme got information from his deputy surveyors, although not as much or as quickly as he wanted. Charles Ashcom and Israel Taylor were slow to provide maps or lists of surveys, because Holme was entitled to a third of the fees they earned for each survey, and by documenting their work they would have to pay up.

There were few accurate maps of the Delaware valley at this time (which was one cause of the boundary dispute between Penn and Lord Baltimore). The best available was a map of Maryland made by Augustine Hermann for Lord Baltimore in 1660. It showed good detail, although Hermann complained of his engraver “defiling the prints with many errors.” 1

When he had enough information Holme drew the map, possibly on sheepskin, and sent it to England to be engraved, as there was no one in Pennsylvania at the time with the skill. 2 A letter of Holme’s in October 1686 referred to his intention to send it soon, and by May 1688 it was advertised for sale in the London Gazette. 3. The last survey included on the map was done for Jacob Pellison in February of 1686/87. 4

It was engraved by F. Lamb and published by Robert Green and John Thornton. The maps were five feet wide, came on seven sheets of paper, and cost 10 shillings. They were offered for sale in London, and it is possible that no copies were sold in Pennsylvania at all. 5 There is no record that Holme ever saw a printed copy of his map.

- Edward Mathews, Maps and mapmakers of Maryland, 1898. ↩

- It is claimed that Holme drew his map of Philadelphia on sheepskin, so he probably did the other map that way as well. Silvio Bedini, Thomas Holme (1624-1695) Pennsylvania’s First Surveyor General. ↩

- John Jordan, Colonial and Revolutionary Families of Pennsylvania, p. 340. Jordan believed that the map was published in a series of editions, of which the earlier ones are missing. This is erroneous, according to Klinefelter. ↩

- At the time the year started in March, so Holme would have called this 1686, but in modern dates it is 1687. Since Quakers used numbers for the months, instead of pagan names, Holme actually would have called it 12th month 1686. ↩

- Walter Klinefelter, Surveyor General Thomas Holme’s “Map of the Improved Part of the Province of Pennsilvania”, in Doud & Quimby, Winterthur Portfolio 6, 1970, pp. 41-74. ↩