Someone who owned land in early Pennsylvania got it in one of three ways: buying it from William Penn, buying it from someone else, or inheriting it. A very few people also got land as a gift from Penn; it helped to be related to him or his wife. 1 This post will discuss the process of buying land from Penn.

Some people, mostly Friends, bought rights to land from Penn before he emigrated in 1683. These people are called First Purchasers. Most of them were entitled to a city lot and land in the Liberties by virtue of their purchase. They did not buy land in a specific place, but rather the right to have their acreage laid out for them. Many of them emigrated and settled on their land, but others sold their rights to others. In either case people held rights that they could bring to Pennsylvania and convert into land.

When someone arrived with rights to land and wanted to have the land laid out, they went to William Penn in Philadelphia (or his Commissioners after he went back to England in 1684), showed him their deed, and requested their land. On this request, Penn or the Commissioners would issue a warrant to Thomas Holme, the surveyor general, to lay out the land. A typical warrant would look like this:

“William Penn, Proprietor and Governor of the province of Pennsilvania and the territories thereunto belonging. At the request of Joseph Willard in right of his brother that I would grant him to take up his City Lotts where they fell to build upon it. These are to will and require thee forthwith to survey or cause to be survey’d unto him the Lotts proportionable to his Purchase; and make returns thereof into my secretary’s Office. Given at Philadelphia, the 8th 9br 1683. William Penn. For Thomas Holme, surveyor general.” 2

Note that Joseph’s brother George was the actual purchaser and that Joseph was requesting based on George’s right. (George was a First Purchaser of 1250 acres.) Also note that city lots were laid out in different sizes depending on the size of the purchase; 1250 acres was above the average. 3

Once the warrant was in Holme’s hand he could either survey it himself or pass the job on to one of his deputy surveyors. In either case, once the survey was done, a return was filed with the secretary. A return was a description of the land, where it was located and how many acres it contained. A typical return would look like this:

“By the Surveyor General’s order pursuant to two warrants from the Commissioners dated the 10th of the 12th mo 1684 and the 11th of the 6th mo 1685 I certify that I have surveyed unto Denis Roachford [Rochford] a certain Tract of Land scituate att Moose Lickamickon begining at a post in the line of the land of John Barnes thence northeast by the same and other lands 960 perches to a large oke [oak] marked for a corner thence northwest by vacant land 700 perches to a large hickrey marked for a corner then southwest by vacant land 960 perches to a white oke for another corner thence southeast againe by vacant land 700 perches to the place of begining qt [quantity] 4200 Acres the 15th 6th mo 1685. Tho Fairman surveyor.” 4

This description of the boundaries is called the metes and bounds. Note that they spell out exactly where the land is, if you can find the post on the line of John Barne’s land. (It would be somewhere near the boundary of modern-day Hatfield and Montgomery townships in Montgomery County.) A perch was a unit of both acreage and length. Seven hundred perches is just over two miles. This was a very large tract.

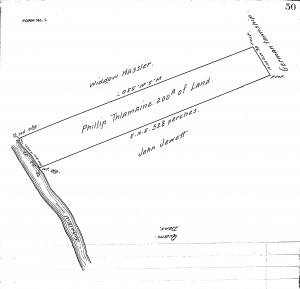

Along with the return the surveyor would make a survey, a map showing the land, adjoining landowners. Here is a sample survey, from the later copies available online. 5

Note that the copyist in the 1800s had the usual trouble with the name of Philip Theodore Lehnmann, creating a non-existent Thlamaine. This tract was typical of one fronting the navigable rivers, with a short strip along the river, extending backwards from there. There was no date on this survey; it may have been done in 1682. He mentioned it in his will in early 1686.

The survey was returned to the Surveyor General’s office, along with the return. The purchaser did not keep it; at this point he had no written proof that he owned the land. 6 The Surveyor General was supposed to check the survey to make sure it laid out the proper number of acres, and to keep it on file in his office.

The final step in the process was for the landowner to apply for a patent. This was the written proof that he owned the land. It included the description of the metes and bounds, and the legal text indicating ownership. Here is a sample of the patent for Mary Southworth’s city lot.

William Penn… Governor… to all to whom these presents shall come sendeth greeting: Whereas there is a certain lott of land in Philadelphia scituated in the third street from Delaware [river] containing in breadth forty nine foot and a half and in length two hundred fifty five feet bounded northward with Chestnut Street, eastward with Thomas Rouses land… granted by warrant from myself bearing date the 6th day of the 4th month 1684 and laid out by the Surveyor General order… unto Mary Southworth… Know ye that I have given granted and confirmed by these presents… Mary Southworth her heirs and assigns forever… paying one English silver shilling… 31st 5th mo 1684. Recorded 7th 6th mo 1684. 7

Note that Mary owned the land outright and could bequeath it to her heirs or sell it to someone else, but she had to pay a quitrent of one shilling per year to Penn. 8 9

The next post will show how to find the early land records: warrants, surveys and patents.

- Penn did make a few gifts of land to others, such as John Aubrey, who wrote in 1686 that William Penn gave him 600 acres in Pennsylvania “without his seeking or dreaming of it”. (Memoir of John Aubrey, by John Britton). Penn, a member of the Royal Society, though no scientist, admired Aubrey’s work. ↩

- Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Archives, online at http://www.phmc.pa.gov/, Land Records, Copied Survey Books, Book D-80, page 43 (image 85). ↩

- The month name 9br referred to the ninth month—November—since prior to 1752 the year started in March. ↩

- Copied Survey Books, D-86, page 191, image 96 ↩

- Copied Survey Books, D-79, page 99, image 50 ↩

- Donna Munger, History and Guide for Pennsylvania Land Records, p. 46. ↩

- Exemplification Book 1, Philadelphia City Archive. ↩

- Penn used these rents, widely resented and often not paid, to raise revenue in lieu of taxes. The Blackwell Rent Roll was an attempt to catalog the rents due, in hopes of collecting them more systematically. ↩

- Mary’s brother John Southworth was an apothecary and clerk of the Philadelphia monthly meeting. ↩